FilmFarsi Golden Age

Marjane Satrapi's Carte Blanche in 2021 allowed us to rediscover Prince Ehtejab, the bold iranian cinema masterpiece that reminded us that an art form was suppressed at birth by the islamic power. Though the West tends to consider that Iranian cinema only started in 1979, the country's film industry began in 1900 and went through several very différent inspiration phases, from the very subversive, to the more entertaining. The early 50s saw the birth of one of the most popular waves, called filmfarsi, the word farsi at first describing foreign films poorly dubbed in Persian, and later derisively a whole category of national productions, somewhat similar to Bollywood films mixing song, dance, romance, melodrama and fight scenes. The filmfarsi wave lasted till 1979.

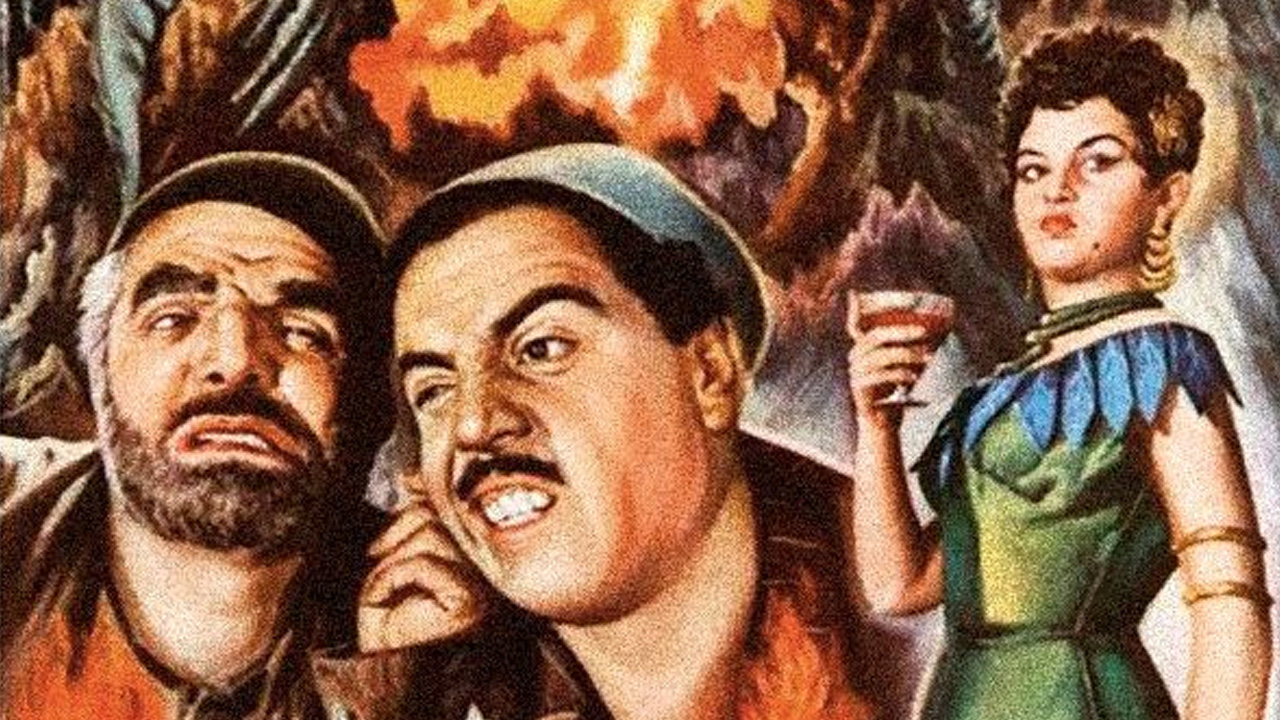

A filmfarsi is characterized by a mashup of several popular cinema genres, Western or local, with a taste for recycling that gives birth to a totally impure art form where comedy can turn to drama and drama turn into unusually trivial farce. Often improvised from production to shooting, using limited sets, farsi films navigate between B and Z genres, in a hopscotch of zooms and borrowed soundtracks. Featuring the lower classes (the middle class is hardly represented), it usually opposes village life purity to corruption, which might explain the phenomenal success of a genre despised by intellectuals and the government. Be they set in villages (The Farm Nightingale (1957), The Village Song (1961), The Sparrows Return to the Nest (1963)), or family melodramas (The Vagabond (1952), The Mother (1952), Neglected (1953)) or fantasy farces (A Night in Hell (1959), The Fugitive Bride (1958), I Could Die for Money (1959), A Star has Shined (1963)), the same plots and models recurr repeatedly with stereotyped masculine figures, cruel and/or courageous men, idiots, bandits, murderers, always on a quest for redemption, amounting to moralising or corny endings. As for women, when they aren't mothers, they're whores that the men will set on a righteous path. An essential figure embodies this "savior", a bad boy symbolizing both patriarchy and religious authority: the Jahel. To further this schizophrenic approach, typical of Iran in those days, if the loose woman must be redeemed, she must first be shown in her life of sin, thus giving female viewers an image of false feminine freedom and all spectators an opportunity to contemplate her vices. A summit of the recurring paradoxes of filmfarsi: the veiled woman wearing a miniskirt. As Ehsan Khoshbakht, historian and director of the documentary Filmfarsi, says, at the beginning of the revolution, not just women were veiled but culture too: movie theaters were burned down, films and equipment destroyed, and the only way for the following generations to discover them was by buying illegal VHS tapes. Here are a few traces of a cinema that wasn’t totally suppressed, but biffed out, erased, with most of its actors, in fear of being arrested and executed, forced into exile. In view of our current conjecture, must history always repeat itself?